Primarily, an interest rate is the compensation a creditor requires for credit risk. Credit risk comes in several forms: there is compensation for the loss of possession of the use of a medium of exchange (what some economists term time-preference), there is the risk of non-settlement by a debtor, and there is the risk of loss of purchasing power of the medium of exchange over the period of a loan.

It is the sum of these three elements which value credit at a discount today compared with its eventual realisation when possession returns to the creditor, nowadays always expressed as an interest rate.

That is the function of an interest rate. It puts a price on tomorrow’s values today. It is something to be determined between debtor and creditor and is never the business of anyone else, let alone a central bank. But we need to go further and demonstrate that the errors of interest rate management are even greater than insisted by those of us who understand that the preceding description of the role of interest rates is correct. The answer lies in Gibson’s paradox.

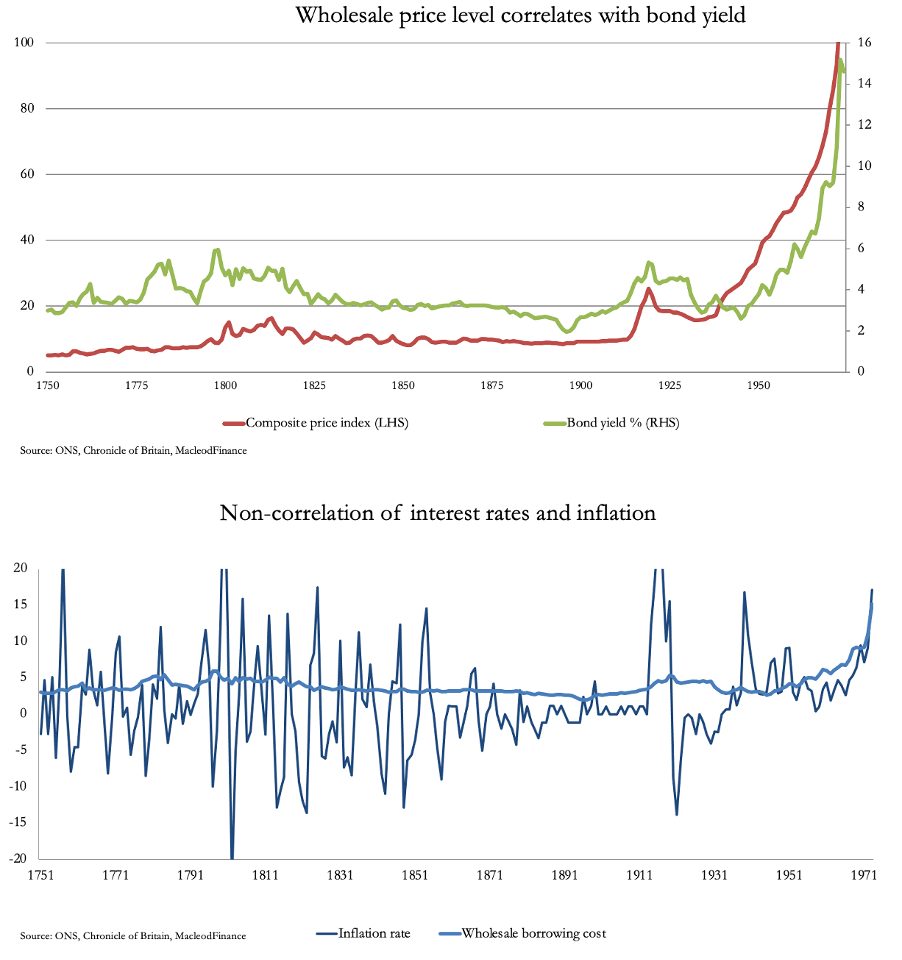

Gibson’s paradox demonstrates that interest rates correlate with the level of prices, and not with the rate of inflation. This is illustrated in the charts below:

It is clear from historical data that interest rates and therefore bond yields correlate, while interest rates, or bond yields, and the rate of inflation do not. Bond yields can be taken as a smoothed approximation of short-term interest rates plus, of course, something for additional credit risk.

Keynes, who named this paradox after fellow economist Arthur Gibson, wrote in his Treatise on Money that it was "one of the most completely established empirical facts in the whole field of quantitative economics". He called it a paradox because he could find no explanation for it, and both Irving Fisher and Knut Wicksell also failed to explain it. Clearly, preconceived economic notions by economists rather than a practical understanding were the problem.

The short explanation is simple and can be explained by the interests of both debtors and creditors. The creditor position I have described above, and from that it should be clear that in its discount form the role of an interest rate is to compensate the creditor for his expectation of a change in the value of the obligation owed to him while that obligation exists. He will be assessing what goods and services that units of credit will buy at a future date, and not the rate at which it changes.

To appreciate the position of the debtor, we must look at it from his point of view and assume that his motivation is to deploy debt profitably. Let us say that the borrower plans to use the funds to invest in production. At the outset, he will know his trade and can make the necessary estimates of cost of production, the value of final sales, and therefore the cost of borrowing he is prepared to pay in order to secure his profit. Otherwise, there is no point in borrowing funds, and indeed the cost of funding is a yardstick he will probably apply to his own capital invested in the project.

Because he assesses his costs, he knows at what level of interest the project becomes uneconomic. Therefore, he will be prepared to bid up for credit to a certain limit, the whole enterprise being dependent on the value of the project’s output. He knows today’s prices, and he might make some assumptions about how prices in the future might differ. But clearly, it is his expectation of the final value of units of output that determines the interest cost he is prepared to pay. In other words, the two must correlate.

That is the explanation of Gibson’s paradox. It is not a paradox at all, but a reasonable description of commercial reality and how it is reflected in credit. It is most evident under a gold standard, when long-run price levels don’t alter much on balance. This has led other writers, notably Barsky and (Larry) Summers in their often-quoted 1980s paper to conclude that it is a feature of the gold standard. The error is common among economists of not appreciating that it is the statistical distortions under a fiat currency regime which make evidential comparisons impossible. And this is the trap into which they all fall.

To obfuscate the issue even further, bank credit today is expanding for non-productive use — bolstering consumer spending falsely and funding financial speculation. Nonetheless, it should be clear why from every angle of attack, manipulation of interest rates by central banks fails in their objectives and can only make things worse.

Is there any role for central banks in managing interest rates? The answer is a qualified yes, if to illustrate it we go back to the days of gold standards and the debate between the currency school versus the banking school. The currency school’s position was reflected in the 1844 Bank Charter Act, whereby Parliament appointed the Bank of England for a further term as the government’s bank. Under the Act, the Bank was required to split itself into two departments: the issue department and the banking department. The issue epartment was required to maintain gold backing for the sterling notes in public circulation, for which they given a virtual monopoly. They were further required to exchange notes on public demand for sovereign coins valued at one pound.

There were two problems with this arrangement. It failed to appreciate that the bulk of sterling redemptions for gold (and vice-versa) were not for banknotes, but by cheque presented at the Bank for exchange of bullion. A run on the bank’s reserves could therefore become extremely rapid, which was not anticipated. The second problem was that the Bank’s interest rates were under the control of the banking department, which would deploy them to manage the Bank’s relationship with the London banking system. Consequently, they would lower interest rates in the event of a banking crisis.

It was soon found that when the banking department lowered its deposit rate, there would be a run on the issue department’s gold reserves. The reason was simply that the interest rate differential with other centres would set up a gold arbitrage. If, for example, gold could be obtained at three per cent from the Bank and it would fetch six per cent in Paris, it was profitable to exploit the difference. Therefore, there was an unavoidable conclusion:

The role of interest rate management was solely to manage the gold reserves.

Today, we don’t have gold standards. But if you want evidence that the role of interest rates has not changed in a fiat currency context, look no further than why in recent years the dollar has been strong against other currencies, and in particular why it is that the yen has fallen from 112 to the dollar in early 2022 to 161 today. Why? The Bank of Japan has refused to raise official rates while at the same time they were increased by the Fed from zero to 5.3% today.

Because no one could understand Gibson’s paradox, central banks have persisted in making the error of using interest rates in an attempt to control inflation or save the banking system in crisis — economic outcomes. In monetary affairs, we really are in the kingdom of the blind.

As an addendum, it will be easy for Russia to reintroduce and maintain a gold standard for the rouble. Russian banks simply buy gold in western markets where the lease rate is less than 2%, transport it to Moscow, and submit it to the central bank in return for roubles currently paying 16%. The point is that on a proper gold standard, the rouble becomes a gold substitute, and therefore nearly as good as gold itself, at least to a Russian bank. As reserves mount, the central bank can then reduce the interest rate level to maintain the desired balance of gold reserves.

This will be a choice that Russia will have to make in order to prevent the rouble being destroyed as a fiat currency when the dollar is eventually rejected in the markets and returned to its maker (i.e. the Fed). But it is one thing when the Russian government’s debt to GDP is only 21% and the budget is generally in surplus (other than for temporary war finance). But it is another matter for fiat currencies whose managers don’t understand the role of interest rates, use them to mismanage the economy, and have a government hopelessly bankrupt without passing laws to end mandated unaffordable welfare.