Because central banks are the root of the modern money tree, they can use entries in their gold revaluation accounts to turn into capital, pay for expenses, or transfer it to their respective Treasuries. In addition, gold revaluation accounts can be used to cancel government bonds held on central bank balance sheets to lower the public debt.

Multiple large central banks are currently operating at a loss while public debt levels are elevated. In this article we will examine how central banks' gold revaluation accounts can offer solace in these challenging financial environments. Central banks’ accounting rules are but fictional obstacles, as these are self-imposed and can be discarded.

Introduction

What is also of interest is the revaluation accounts. … The most important revaluation item of course is … gold. In fact, the value is about €180 billion euros above the cost of purchasing it, … and it’s part of the considerable own funds of Bundesbank, underlining the soundness [of our balance sheet]. So, in fact, it’s on firm ground, the balance sheet of Deutsche Bundesbank, and this certainly makes it easier for us to bare losses over a certain period of time.

Wuermeling’s statement highlights Buba’s GRA as its solvency backstop. Previous to this statement Buba suggested that the prevailing accounting rules of the European System of Central Banks prohibit GRAs from being used for anything other than offsetting unrealized losses in gold. Now, by speculating to use their GRA to offset general losses, the Germans can’t be bothered by the rules, whatever they are.

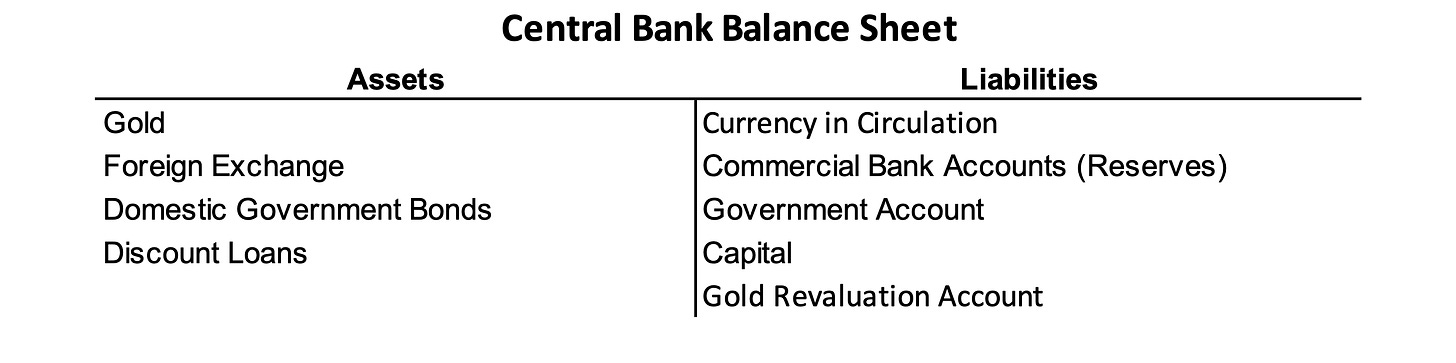

Central Bank Balance Sheets and the Gold Revaluation Account

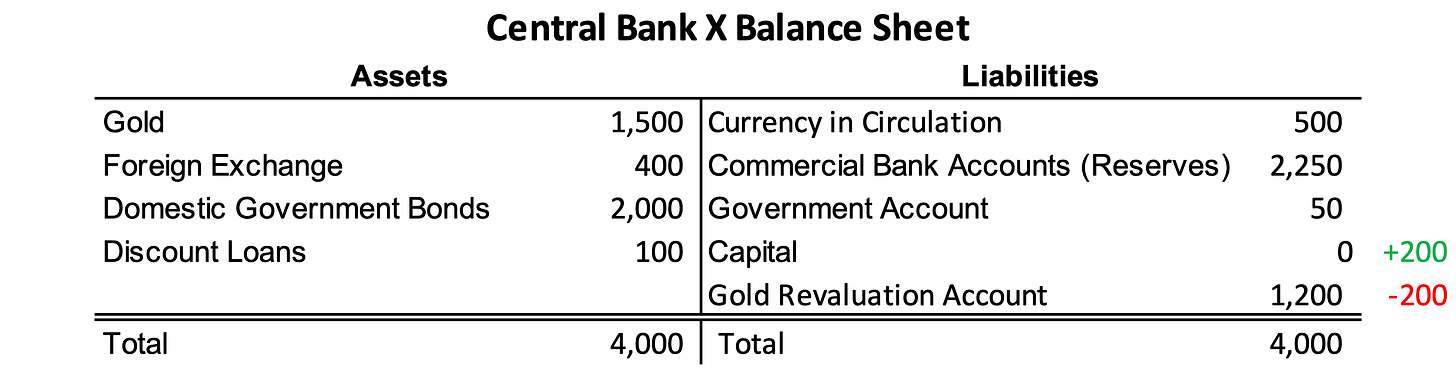

Relevant to our present discussion: Currency in circulation are coins and notes. Reserves are currency in book-entry form and represent funds that commercial banks hold at their central bank, used to clear interbank payments, or to be converted into physical currency. Currency and Reserves form a country’s monetary base (base money). Next to commercial banks, the national Treasury has an account at the central bank, often referred to as the Government Account. Capital is the central bank’s financial buffer, swelling when profits are made, and shrinking when losses accrue. Gold reflects the value of the central bank’s gold assets. Domestic Government Bonds are bought by the central bank in the open market to conduct monetary policy (or finance the government). We will pretend the central bank has two types of customers: the government and commercial banks. Finally, Capital plus the GRA makes up the central bank’s Equity.

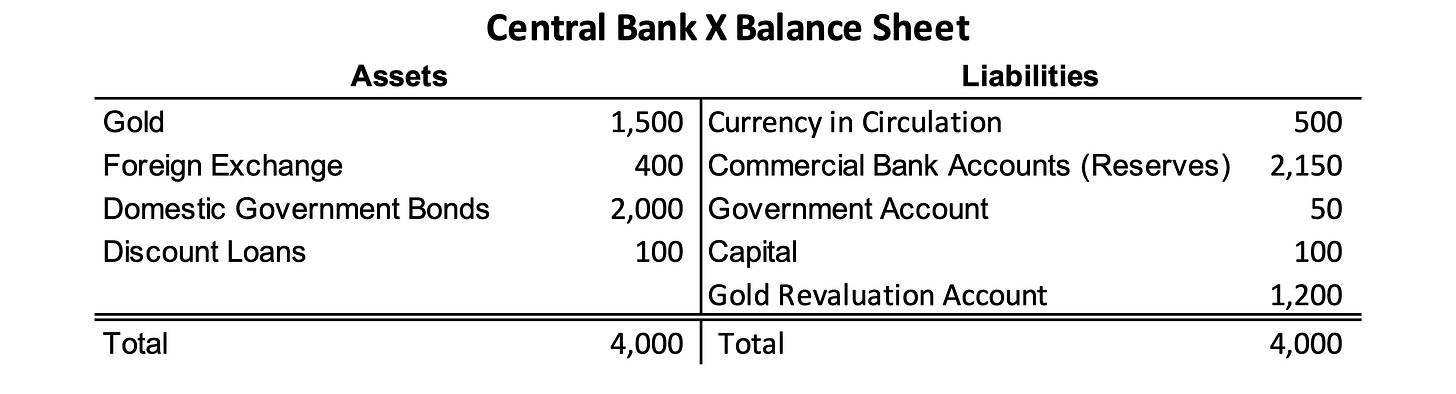

Regarding the GRA, suppose the central bank of country X (CBX) buys 300,000 troy ounces of gold for $1,000 local dollars per ounce, at a total cost of $300 million. In thirty years' time the gold price rises by 400% to $5,000 dollars an ounce. The value of CBX’s gold has gone up to $1,500 million, and its unrealized gains to $1,200 million ($1,500 million minus $300 million). Reiterating, a GRA keeps track of the unrealized gains on gold assets—in our example at $1,200 million.

GRA = present gold value – historic gold purchasing cost

Central bankers will typically say the GRA is used for cushioning downturns in the value of their gold (page 26). If the gold price declines, the GRA shrinks (as well as the value of gold assets), and the central bank doesn’t have to record a loss on its gold. But, as we will see later on, GRAs can be deployed for a variety of alternative uses.

To wrap our heads around the applications for GRAs, we need to understand the balance sheets of central banks, but also their cash flows and ability to create (“print”) base money. Because central banks can create money, they can also turn GRAs into money. The following is highly simplified.

Central Bank Cash Flows

By example, CBX earns $10 million dollars in interest on Domestic Government Bonds it holds as assets. To collect money (income) from the Treasury, CBX debits the Government Account and credits its Capital. In turn, CBX has to pay $10 million in interest on Commercial Bank Accounts—to set monetary policy central banks pay interest on their reserve liabilities. This interest (expense) is disbursed by CBX through debiting its Capital and crediting Commercial Bank Accounts. All else equal, in this example CBX breaks even on its income and expenses.

If CBX’s income transcends its expenses, it can choose to allocate this profit by increasing its Capital, or transfer funds to its largest shareholder through increasing the Government Account. In case expenses are higher than income, CBX has to tap its Capital.

From these examples of cash flows, and what we have discussed prior, we conclude a central bank’s Equity comprises of realized gains (Capital) and unrealized gains (GRA).

How Central Banks Can Turn Gold Revaluation Accounts into Money

In one of my previous articles on this subject I reported how the central bank of Curaçao and Saint Martin (CBCS) sold and immediately bought back some of its gold assets in 2021. Through these transactions CBCS was able to circumvent the accounting rules and move entries from its GRA to its Capital to cover general losses.

When I further investigated how central banks operate, I realized that in the absence of their self-imposed accounting rules, GRA entries can be moved to a central bank’s Capital with the stroke of a keyboard. It’s just numbers. As long as a central bank’s balance sheet stays in balance—shuffling with liabilities won’t change that—not a single ounce of gold has to be sold to use a GRA for expanding its Capital.

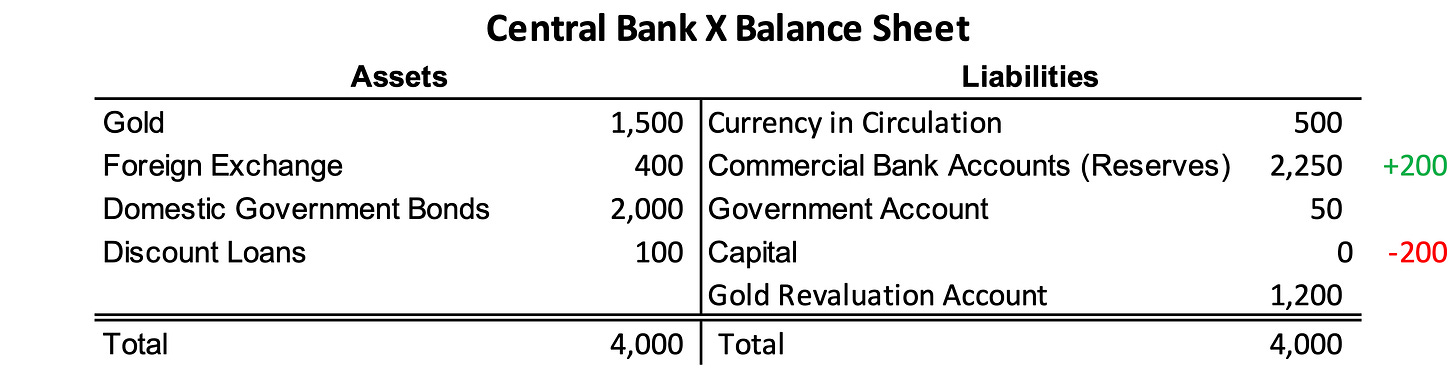

Imagine CBX has to pay more interest on its reserve liabilities than it receives on its Domestic Government Bonds year in year out, drawn from its Capital until its financial buffers have reached zero. Going forward, making losses with no buffers, CBX has two options.

One, CBX can print money to pay for expenses, which would be recoded as a loss and result into negative Capital*. Because CBX has the ability to print money indefinitely it can continue to operate under negative Capital, though this route is risky: the market can lose trust in CBX— with all due consequences—if it smells out CBX is printing money to bail itself out instead of conducting monetary policy.

Two, CBX can scrap the accounting rules, and debit its GRA to credit its Capital. Subsequently, it can keep paying interest on Commercial Bank Accounts without going into negative Capital. This avoids the danger of a financial meltdown as a result from negative Capital.

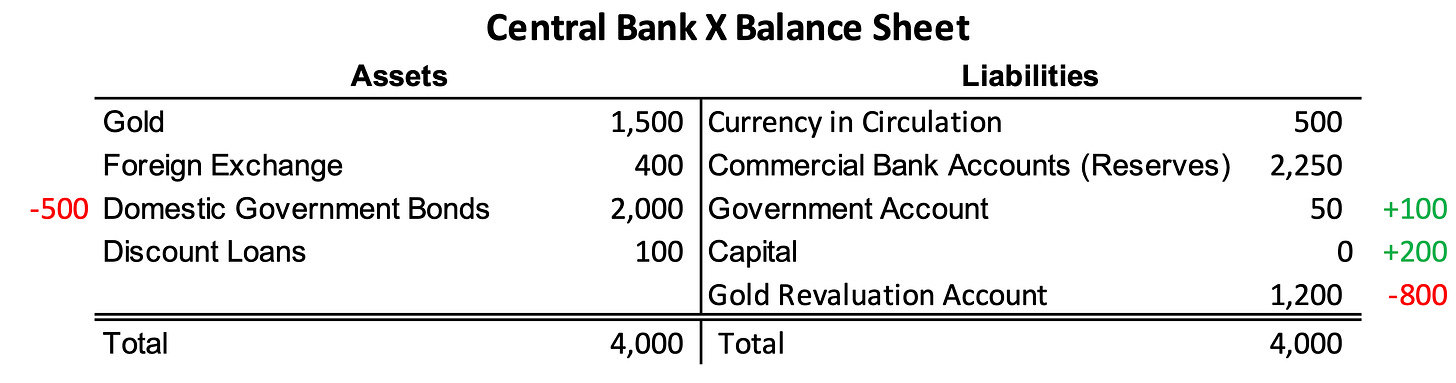

Considering, in our simplified example, central banks only have two types of customers, expenses can either be transferred to the Government Account or Commercial Bank Accounts. In the latter option base money is directly increased. Entries first distributed to the Government Account and from there to Commercial Bank Accounts (through the Treasury spending in the economy) expand the monetary base as well. It is this base money creating feature that allows central banks to transmute unrealized gains into realized gains by rearranging their liabilities. Though, using GRAs to cover losses does not always have an effect on the monetary base.

Gold Revaluation Accounts to Support Government Budgets

Furthermore, in case the public debt has become unsustainable, CBX can cancel Domestic Government Bonds on the asset side of its balance sheet and offset these losses by decreasing its GRA (debt relief). In this very example no base money is created.

The final option for CBX would be to print money to buy gold from the private sector (“gold QE”) and drive up the gold price (devaluing its own currency against gold). In the process its GRA will grow, allowing more Domestic Government Bonds on its balance sheet to be cancelled, or Capital to be incremented.

Historical Examples of Uses for Gold Revaluation Accounts

In the 1930s, the Netherlands was one of the last countries to abandon the gold standard. When it finally did, and the Dutch guilder was devalued against gold, the Dutch central bank (DNB) was sitting on a GRA of ƒ221 million that could be used freely because gold could not fall below its new official price. In 1940, the largest chunk of DNB’s GRA, ƒ117 million guilders, was transferred to the Treasury. About ƒ30 million was used to cover general losses, and the remaining ƒ75 million was allocated to a stabilization fund**. DNB could do as it saw fit with its GRA, and plenty other central banks at the time did likewise (page 72).

More recently, in 2002, the central bank of Italy made a loss of €22,000 million, resulting from the conversion of old government debts held on its balance sheet. In order to absorb the loss, Banca D’Italia drew €13,000 million from its GRA (page 309).

Lebanon’s Treasury received funding from its central bank’s GRA in 2002 and 2007 (page 72).

The central bank of Curaçao and Saint Martin bypassed the accounting rules and moved entries from its GRA to its Capital to cover general losses in 2021.

Conclusion

Foreign currency revaluation accounts are not used to replenish central bank Capital because such unrealized gains may be temporary. With gold revaluation accounts, however, it’s a different story. Gold is the only internationally accepted financial asset that can’t be printed. As a consequence, the gold price denominated in fiat currencies always goes up in the long run, perpetually increasing the size of GRAs. In fact, there is no limit to GRAs.

Buba’s GRA is about €176 billion, and the historic cost of the gold was €8 billion (the gold was purchased at an average price of €74 euros per ounce). If Buba makes the assessment that the gold price is not likely to ever go below €500 an ounce—at the time of writing gold trades north of €1,800—it can draw €46 billion from its GRA to recapitalize itself with impunity. That’s a more compelling option than asking taxpayers for €46 billion, let alone printing money and dipping into negative Capital.

Accounting rules that leave no room for utilizing GRAs should be taken with a pinch of salt. Monetary authorities regulate themselves and accounting rules are changed all the time, especially during crises. Or central banks can figure out a workaround like in Curaçao.

I guess in the eurozone the rules can be easily circumvented, which would explain why the Bundesbank prepositions itself by targeting its GRA as “own funds” (Capital), and how Banca D’Italia could use its GRA to cover losses in 2002. Although I am not a lawyer, the ECB guidelines seem to tolerate evasions.

Notes

**Source: Vanthoor, W. (2004). De Nederlandsche Bank 1814-1998.