We have a new government in the United Kingdom, and in a few months’ time there will be a new President in the United States. It matters not who becomes US President; either of the two leading contenders will make the basic errors already apparent in the UK’s new socialist government. And that is having the belief, or the self-given right, for a government to intervene in an economy for whatever purpose.

Assuming for a moment that a government’s intention is to intervene solely in the interests of the electorate, even then it pursues an impossible mission. It has no role in commerce except a disruptive one. It seeks to manage its citizens’ affairs, when the only parties who can effectively do so are the citizens themselves.

Anyone setting out to govern with the best intentions is doomed to failure. He or she, and all their advisors make the error of thinking that macroeconomics is a valid science and that statistics quantify economic reality. It confuses an unquantifiable human science with a mathematical natural science.

Macroeconomics was invented by Keynes, having twisted Say’s Law to distort reality. He had to do that to justify an interventionist role for government. Say’s Law is not, as Keynes put it, “…equivalent to the proposition that there is no obstacle to full employment”. Say’s Law merely points out the basis for the division of labour, whereby we specialise in making something which we believe will be demanded by others for profit.

Keynes used deception to detach production from consumption, leading him to argue that falling consumer demand created unemployment, when instead it is falling production that creates unemployment. The reasons why production might decline, leading to rising unemployment are basically down to the misallocation of credit, not something which a government can correct, and something Keynes appeared to have wilfully misunderstood.

Out of Keynes’s new economics, macroeconomics, the blunder arose that on the one hand there were unemployed workers unable to spend, and on the other that there was an accumulating glut of unsold goods. This glut was expected to undermine prices, deterring consumption even further as consumers held off purchases hoping for bargains. This ruled out the possibility that there can be rising unemployment and inflation of prices at the same time, which is patently untrue as history demonstrates.

Keynes’s macroeconomics is so full of flaws that it would require a book-length article to refute them in detail. Suffice it to say that today almost everyone believes this nonsense, including politicians for whom macroeconomics gives the justification for intervention, the denial of free markets, and an increasing role for government.

Politicians recently elected in the UK are led by a lawyer whose skill is to argue a brief right or wrong: that’s what lawyers are paid as prosecutor or for the defence to do amorally. Such a lawyer believes that every problem can be resolved by passing a new law. Starmer’s conditioning is socialistic, being named after Kier Hardy, the founder of the Labour Party. Thus, he is the socialist bureaucrat’s bureaucrat, bent on continuing the advancement of the state in the general interest of socialist ideals. He is comfortable with the EU (he was anti-Brexit) and the EU will be comfortable with him, drawing the UK back into the EU de facto with conforming legislation.

His Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, has a MSc from the London School of Economics, and has worked at the Bank of England. In other words, she is a Keynesian socialist imbued with all the errors that her brief career at the Bank of England implies.

Across the pond, it seems that Kamala Harris is now favourite to become the next President. OddsChecker has her 11/13 on, while Trump has slipped to 11/10 against. Like Starmer, Harris is a lawyer seemingly without a moral compass betrayed by her apparent willingness to say anything to appease and grow her political base. But her betting margin over Trump is too thin currently to regard her as a shoo-in.

Primarily a businessman, Trump has simplistic ideas about reviving US production. He makes the error of believing in his ability to make America great again by intervention. But it is almost always observed that not only do objectives of these sort fail, but nearly always there are unforeseen consequences.

The entire western government establishment has fallen for the macroeconomic myth created by Keynes in his General Theory, irrespective of who is in charge. The error even extends into markets which value the credit upon which the entire system depends. It is merely a question of how rapidly today’s politicians working with like-minded permanent establishments force the pace of unconsciously collapsing these erroneous theories, a process which is rapidly moving towards an endpoint.

Bad terminology

The etymology of the noun recession is derived from the verb to recede, which means to move away from a previous position. In economic jargon it has replaced words such as depression or slump, which more accurately describe an economic condition. An economy doesn’t move in any sense: it can only progress or decline in its level of activity. The use of the term recession is meaningless and misleading.

You might think it hardly matters, but the word also deflects attention from the cause of so-called recessions. It is all to do with the supply of bank credit. The economic cycle reflects a cycle of bank credit, which has been evident since semi-reliable records have been available.

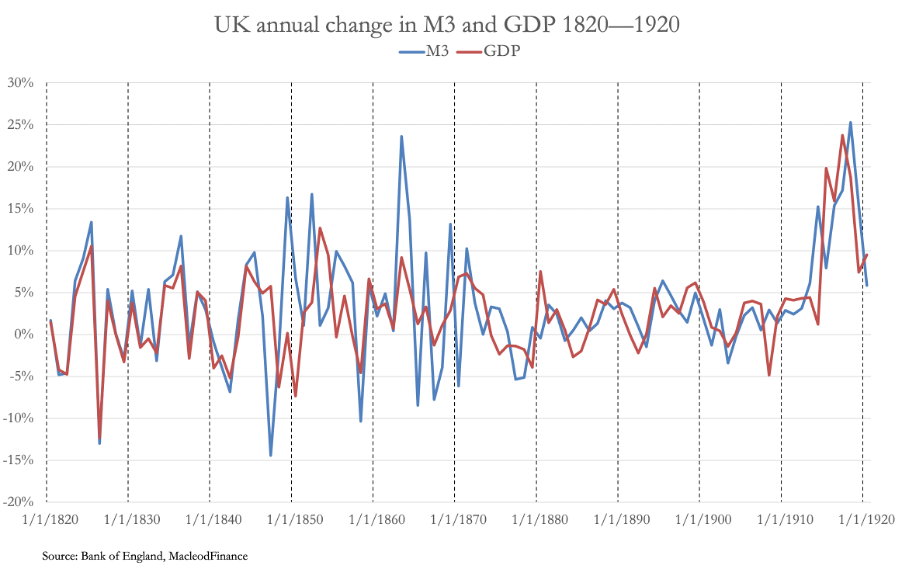

The chart above reflects a century of changes in the bank credit cycle and its remarkably close corelation with changes in GDP mostly under a gold standard (1821—1914) until 1920. Clearly, it is the willingness of banks to extend credit which drives the economic cycle, with changes in the level of bank credit leading changes in GDP. This was known to credit analysts before Keynes’s invention of macroeconomics.

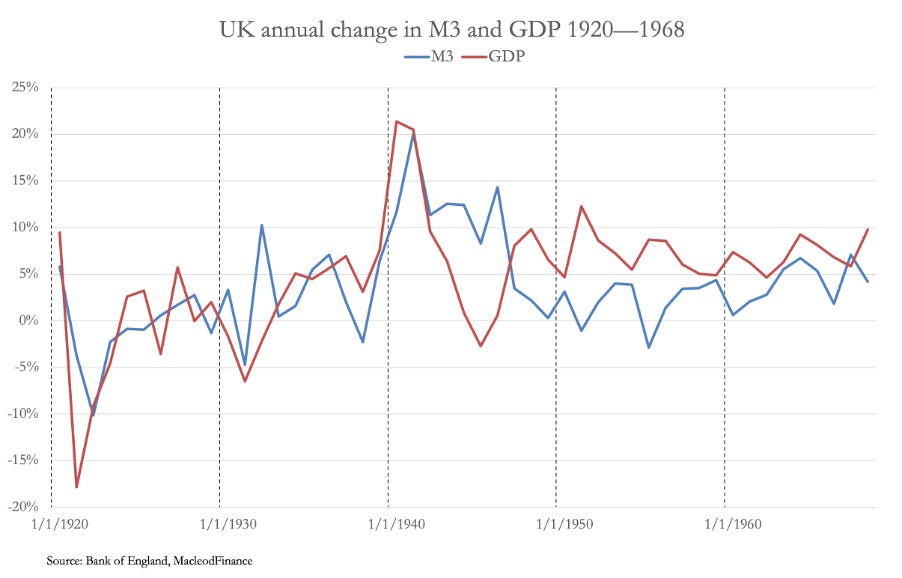

The relationship still held into the Second World War. But post-war, Keynesian policies of trying to stimulate economic activity by deficit spending were being implemented, appearing to turn the relationship upside down. This is shown in the next chart.

But all deficit spending does is add base money into the economy, thereby bolstering GDP artificially. Bank lending may not decline so much, but that is perhaps because riskless lending to government and government agencies. State guaranteed loans become possible. But government spending is simply non-productive, and besides stimulating a few government-chosen industries it is otherwise economically destructive compared with an economy free from government meddling.

For proof of this statement, you need only observe the dynamic post-war Hong Kong economy, where John Cowperthwaite even instructed his officials not to collect statistics, knowing that they would only lead to destructive interventionism. His free-market approach compares favourably with any of the Soviet economies in Europe or Mainland China which went full interventionist at the same time, causing widespread misery and starvation through misallocation of resources.

Instead of promoting fear of recession as cover for economically destructive government policies, you would think that the lessons of the Soviet failure would have been learned. Not a bit of it: instead, we are told about the supposed failures of free markets and the necessity of regulation and laws to control them. It’s a different form of control from communism, but it is control nevertheless.

The supposed successes of government intervention are reflected in the equally meaningless term, growth. Credit outstanding grows, while an economy progresses. You can measure the credit deployed in an economy, to which GDP actually refers. You cannot measure progress. For an intervening government, growth is a handy lie because a government can inflate total credit deployed in the economy making it appear to “grow”. This is why we have more or less continual growth, which for the UK in its post-war decades exceeded a nominal rate of over 5% at all times (see the second chart above).

Another benefit, for the government that is, is that the fixed rate regime of Bretton Woods allowed it to suppress interest rates and therefore its borrowing costs below the rate at which it was inflating GDP. This was the main reason that UK government debt to GDP fell from an estimated 259% of GDP in 1946 to 74.3% in 1968, while the debt actually grew from £25.3 billion to £34.04 billion.

It is by statistical manipulation and bad definitions that governments pull the wool over our eyes. But that is now coming to an end, because foreign holders of our currencies no longer trust old-school governments. The arrogance with which we assume that foreigners will continue to need dollars and other major currencies is proving our undoing. Taking a moral high ground, we have decided to penalise Russia and China: the first by defaulting on our obligations, and the second on trade grounds and for being in league with the first. Russia has made our theft of its currency reserves widely known in neutral nations, and China has started to sell down dollars by buying gold, energy, and key industrial commodities.

As foreigners catch on, there’s still some $32 trillion dollars and dollar-denominated financial assets in their possession at risk of liquidation. This is happening at peak macroeconomic delusion. Perhaps at the end of it our fiat currencies might become valueless, but hopefully we will revert to calling a spade a spade.